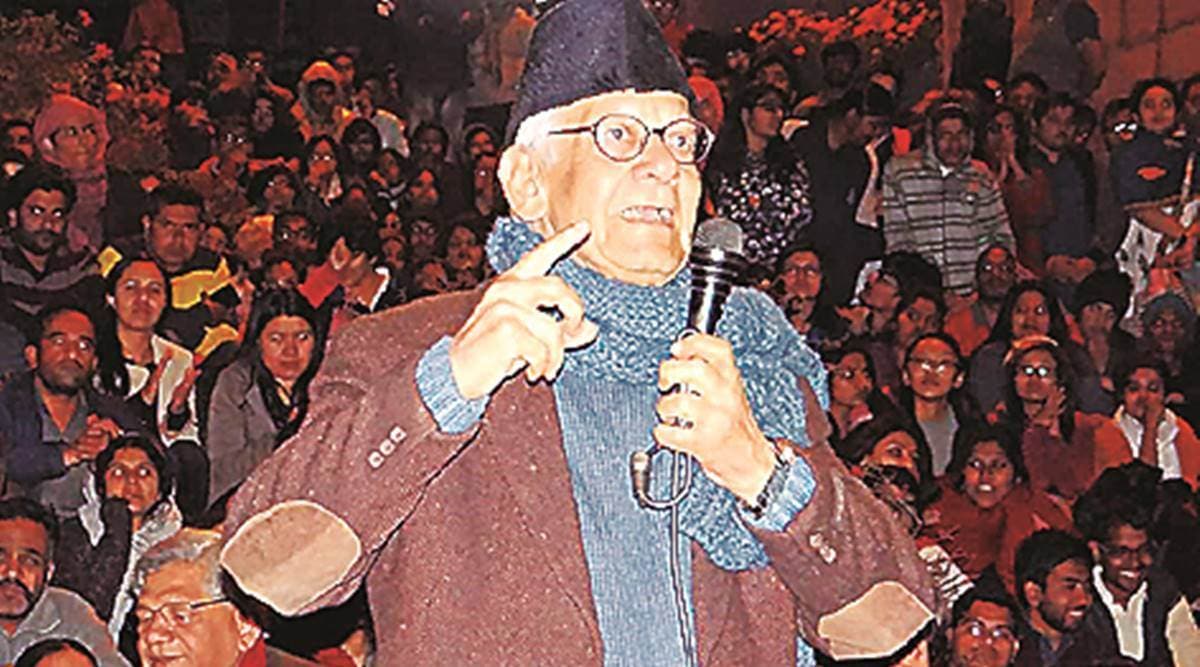

C P Bhambri. (Photo by Samim Asgor Ali)

C P Bhambri. (Photo by Samim Asgor Ali)

In a relationship spanning four decades, Professor C P Bhambhri (CPB) was my teacher, colleague, mentor and friend. When he formally retired from the Jawaharlal Nehru University in 1998, I joked at his farewell that there were four Communist parties in India – the CPI, CPI (M), the CPI (M-L) and the CPB. He often recalled that remark with a chuckle, acknowledging that his particular brand of Marxism was a solo act, hostage to no political party or school of thought.

In the 1970s, in the classroom and beyond, he savaged relentlessly the tradition of behavioural political science which, originating in America, had displaced the extant institutionalist approach to political studies in India. As Susanne and Lloyd Rudolph have documented, in the backdrop of the Cold War and a troubled US-India relationship, the air was thick with speculation about the covert funding of academic research by the CIA. This was particularly so in the field of comparative politics where, led by Gabriel Almond and David Easton, structural-functionalism and modernisation theory dominated the study of politics in developing societies. Rajni Kothari’s Politics in India (1970) was a study in this vein, and Bhambhri’s Marxist critique of it in the Indian Journal of Political Science triggered what was arguably the first scholarly debate in the annals of Indian political science, famously bringing rival ideological perspectives to bear on the analysis of Indian politics. The imperialising propensities of modernisation theory came to be widely acknowledged.

It is possible to discern two phases of CPB’s intellectual journey. His books Bureaucracy and Politics in India (1971) and The World Bank and India (1980) belong to the first phase, in which he addressed primarily a scholarly audience, in a way that reflected strongly the ideological prism through which he viewed the world. In the second phase, which extended over three decades, he was more the public intellectual, seeking to educate public opinion through his newspaper columns, in which historical insights, drawn from a prodigious memory of Indian politics, were woven into the analysis of contemporary issues, identifying continuities and tracing patterns, all inflected by his particular worldview. In both phases, he was a lively and combative intellectual, as staunchly secular as he was staunchly Marxist.

All of these qualities were on full display in CPB’s classroom. He was a conscientious teacher (often punning about his own “class consciousness”) and, apart from punctuality, expected no conformity from students, least of all of opinion. In July 2016, anguished by the events of February that year, he wrote (in these pages) an open letter to students entering JNU. He eloquently described the academic philosophy of JNU — its character as an all-India university, its culture of open debate and the freedom to differ from faculty, its treatment of students as adults and partners in knowledge. These principles were part of his pedagogical and institutional practice.

CPB was quintessentially JNU. I cannot think of another person whose identity was so closely bound up with the institution in the building of which he had been a committed and energetic participant, and whose academic norms he robustly defended, among them the participation of students in university affairs. A man of personal and professional integrity, he was a sharp critic of cronyism, regardless of which ideological stable it came from.

After his retirement, CPB continued to visit the campus regularly, presiding over a shabby little cubicle like an emperor, receiving and entertaining an enormous and diverse range of visitors, listening to grievances and gossip, dispensing advice on how to negotiate workplace intrigues, and offering tea laced with commentary on the news of the day. Nobody entered that cubicle without a feeling of being warmly welcomed and nobody left without a couple of sardonic and freshly minted witticisms about politics and people. Few professors in retirement have so many former students, straddling multiple generations, from India and abroad, calling on them, partaking of such an enormous reservoir of affection.

Although the touchstone of scholarly achievement for CPB was writing a book, that was not sufficient to earn his respect. There was a second requirement, that of intervention in public debate. In this, he subscribed to the highest ideal of the public university as a space where the exercise of democratic citizenship is not just desirable but necessary. To understand social, political and economic developments, and to share this analysis with the larger public was the responsibility of the university teacher. It was one he discharged with conviction himself.

The legacy of Professor Bhambhri endures through his students, whether they are teachers in India and abroad, or political commentators whose writings enhance our understanding of India and the world, or indeed civil servants striving for a better society. Meanwhile, his trademark wit and booming laughter that once echoed down the corridors of JNU are surely enlivening the proceedings wherever he is now.

This article first appeared in the print edition on November 10, 2020 under the title ‘In a class of his own’. The writer is professor, Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi

"lively" - Google News

November 10, 2020 at 08:49AM

https://ift.tt/2JMygzn

C P Bhambhri was a lively intellectual, as staunchly secular as he was Marxist - The Indian Express

"lively" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35lls9S

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "C P Bhambhri was a lively intellectual, as staunchly secular as he was Marxist - The Indian Express"

Post a Comment