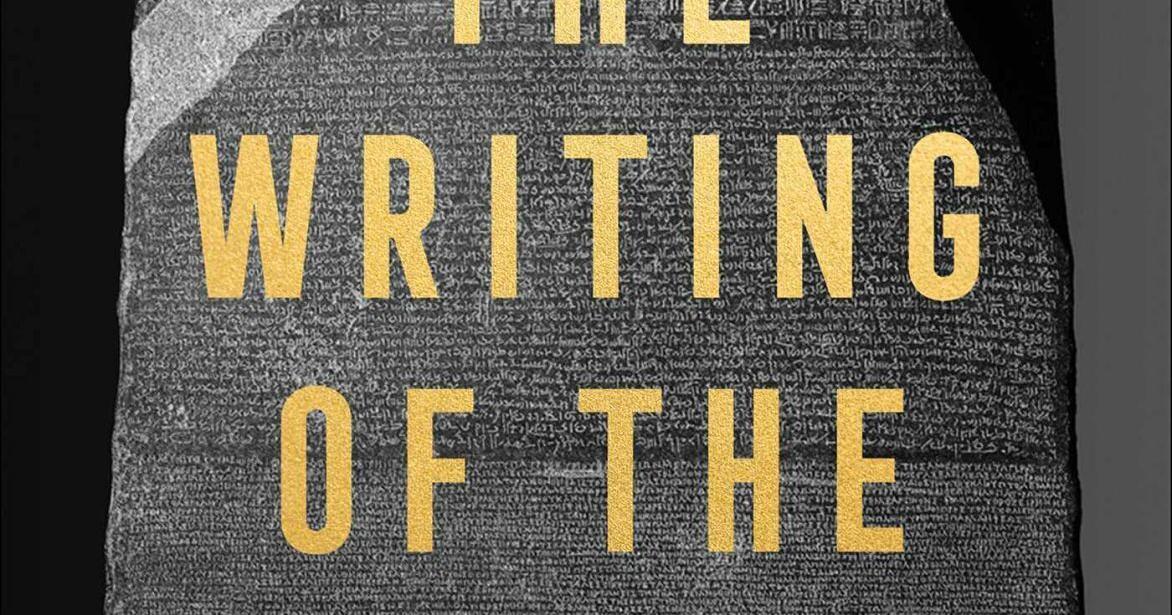

I hope other people enjoy reading “The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta Stone” as much as I did. I expected to learn something about how scholars used the Rosetta Stone to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. I found that and much more: a lively account of the competition between a Frenchman and an Englishman to be the first to accomplish this feat, stories of historical figures and archeologists, and insights into numerous languages, including English.

Author Edward Dolnick is a former chief science writer at the Boston Globe and author of several previous books. He has a remarkable ability to take his reader on voyage of discovery into the unraveling of a long-dead language with interesting side ventures along the way.

The Rosetta Stone, which today sits in the British Museum in London, is a slab of rock that was discovered in the town of Rashid (which the French called Rosetta), Egypt, in 1799. Chiseled into the stone were lines of text in three different scripts — hieroglyphics, demotic and Greek. Nobody had been able to read hieroglyphics for approximately 1,800 years, but many people were intrigued by this mysterious picture-writing that adorned walls and pillars throughout Egypt. Some thought the symbols held some ancient esoteric wisdom. The word hieroglyphics means “holy writing.”

The Rosetta Stone offered the key to this ancient script. While nobody knew hieroglyphics or demotic script, Greek was a known language. If the scratchings on the stone gave the same message in three different languages (or at least three different scripts) then the Greek might be used to decipher the other two.

As it turned out, that was not an easy task. Hieroglyphics was not a simple phonetic alphabet like Greek, Roman or Cyrillic. But it also did not seem to be purely ideographic, like Chinese, where each symbol refers to a single word or concept. Two brilliant men stood out in their attempts to address this challenge. Both were fascinated by and exceptionally adept at multiple languages but very different in temperament and in their approaches to hieroglyphics. “Thomas Young was one of the most versatile thinkers who ever lived, eager to tackle any challenge from any direction. Jean-Francois Champollion was utterly single-minded, unwilling to focus his gaze on any topic but Egypt.” (P. 81) Although Young made early discoveries that were valuable, it was Champollion’s dogged persistence that finally cracked the code of hieroglyphics.

Dolnick follows every step in this process of decoding, sharing with the reader how Champollion discovered that some figures represented sounds, like letters of an alphabet, some were rebuses, like using a picture of an eye to represent the pronoun I, and some were what Champollion called determinatives, like using a picture of a bent-over figure with a cane following the word for old man to drive home the message that that was indeed the intended meaning of that word. Dolnick illustrates his narrative with the actual hieroglyphic symbols.

After his astounding achievement of reviving a dead language, Champollion died young at the age of 43, but not before he had made one more astounding discovery. He found written references to a female pharaoh whose very existence had otherwise been obliterated from history.

I recommend this book to anyone interested in language and languages, puzzles, history, or just lively and engaging writing. It is available at the Manhattan Public Library.

William L. Richter is professor emeritus and former associate provost for international programs at Kansas State University.

"lively" - Google News

February 13, 2022 at 02:00AM

https://ift.tt/eEqGjLv

'Writing of the Gods' retells lively race to decode Rosetta Stone - Manhattan Mercury

"lively" - Google News

https://ift.tt/ejmYCDP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "'Writing of the Gods' retells lively race to decode Rosetta Stone - Manhattan Mercury"

Post a Comment