U.S. natural gas production continues to increase, with more growth expected at least through the middle of this decade to feed new LNG export capacity coming online along the Gulf Coast. Production growth will require new infrastructure, but long-distance transmission lines have become increasingly difficult to build due to entrenched environmental opposition. Meanwhile, gathering pipes have grown in size and length, blurring the lines between gathering and transmission. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll discuss what separates gathering systems from transmission pipelines, why those differences matter, and how those systems are continuing to evolve.

America’s gas production has more than doubled since the start of the Shale Revolution, from about 50 Bcf/d in 2005 to around 104 Bcf/d in 2023. That rise in output began in gas-focused regions like the Barnett, Marcellus and Haynesville, but as more producers shifted to liquids-rich basins, an increasing proportion was produced as associated gas from crude oil-focused wells in places like the Permian, Bakken and Eagle Ford. Those oil-focused wells have become increasingly gassy over time and come with a lot of NGLs. All this has fueled a spate of new gas processing and related assets across the major shale growth basins, with production continuing to set records. As we have blogged about frequently, the U.S. will still need to add a lot of infrastructure — including gathering systems, gas processing capacity and transmission pipelines — to handle all that gas and associated NGLs. We recently covered the gas processing buildout in OMG. We also did a full series last year about the buildout of NGL pipeline infrastructure (see Get Ready) and another series about the pipelines that are increasingly taking gas to the Gulf Coast to help feed new export-driven LNG liquefaction facilities (see Gotta Get Over). Today we focus on gas gathering and transmission networks and we’ll start with a look at the basic functions of each.

Natural gas gathering systems (dashed black oval in Figure 1 below) collect raw, unprocessed supplies from production sites, usually to a central location, often for compression, before most volumes are shunted toward processing and treatment sites. If the gas does not need processing or treating, it gets directed to transmission networks. The gas is usually separated from water and other impurities right at the wellhead. For more treatment, the gathering line carries the gas to the processing plant. We’ve blogged about gathering a lot. A year ago, in Straighten Up and Fly Right, we discussed how rural gas gathering pipelines have increasingly come under federal safety regulations, adding more than 400,000 miles of onshore pipes to the oversight of the Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) starting this year.

Figure 1. Schematic of Natural Gas Transportation System. Source: Canada Energy Regulator

Generally speaking, transmission lines (dashed green oval in Figure 1) move pipeline-quality gas (merchantable gas) long distances from the production area to the wholesale market, where it gets moved further downstream to local distribution companies (LDCs) or other end-users like industrials, power plants or liquefaction terminals. The gas going into a transmission system is often residue gas (associated gas less its NGLs) from processing plants.

Why do those differences matter? Probably the most important reason is regulatory oversight. The Natural Gas Act (NGA), which gives the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) its pipeline jurisdiction, explicitly excludes gathering from FERC authority (even if it crosses state lines), so doing things like changing rates, setting up business practices, or just building a line is much, much easier for gathering than for transmission. Regulation of transmission lines and services by the FERC, on the other hand, is a major headache for operators of interstate pipelines (carrying gas across state lines) and still somewhat burdensome for intrastate systems (confined to transportation within a single state).

FERC is the ultimate arbiter of what can be classified as gathering or transmission and it has had a lot of tests over the years to make that determination. Usually, the wet-dry composition (primarily carbon dioxide, or CO2) change in the stream is the most important factor. So, typically, gathering networks are what’s upstream of processing facilities, while transmission systems are what’s downstream, plus they carry pipeline-quality residue gas. One major exception to that is in the offshore Gulf of Mexico, where FERC allowed some huge deepwater pipelines to be designated as gathering (even though there is no processing between them and their downstream transmission tie-ins) until they converged on their shallow-water outlets into the interstate transmission grid. But onshore, using the processing plant as the dividing line is usually a good bet. And it makes sense because the blood, guts, feathers and other contaminates removed at the processing plant are generally incompatible with long-line transmission.

Let’s take a closer look at each type of pipeline to see how they differ and identify areas where there may be some overlap.

Size and Scope: Gathering systems are typically limited to the areas near production sites, collecting raw natural gas from wellheads and sending it to a processing plant or an interconnect with a larger mainline pipeline. Many gathering systems (but not all) consist of small-diameter pipelines of 20 inches or less, have relatively limited geographic footprints, are designed for specific producers, or plays, and are often operated at low pressure. But growing gas production has led to an increase in dimensions for gathering systems, with pipe diameters and pressures at times comparable to those of transmission networks. As an example, some of DCP Midstream’s gas gathering pipes have diameters of around 30 inches.

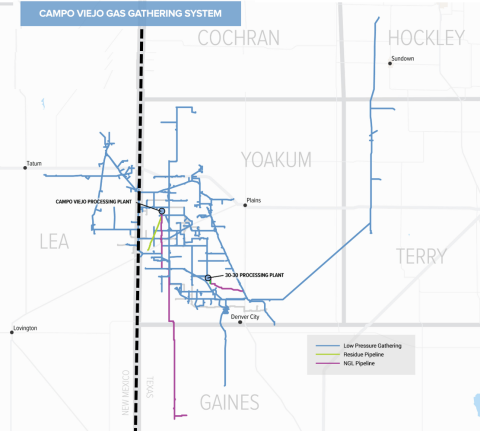

Figure 2. Campo Viejo Gas Gathering System. Source: Stakeholder Midstream

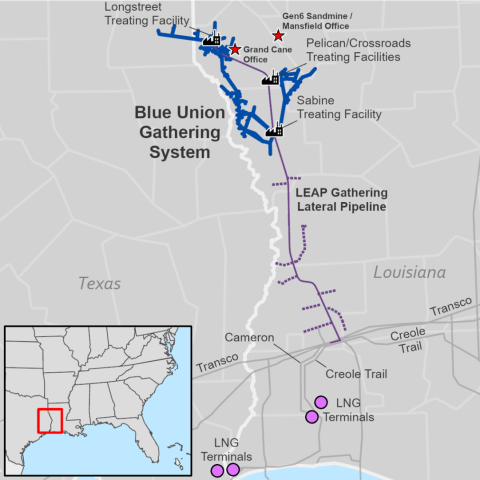

Also, gathering networks usually don’t leave the state but since producing basins don’t abide by manmade borders, some systems do cross state lines, especially in areas with extensive production like the Texas/New Mexico border for the Permian, the Texas/Louisiana border for the Haynesville or the Ohio/Pennsylvania/West Virginia borders for the Marcellus and Utica shale plays. Some examples of gathering systems that cross state borders include Stakeholder Midstream’s Campo Viejo Gas Gathering System (see Figure 2), which serves parts of New Mexico and Texas; Targa Resources’ Permian Delaware network, which spans the same two states; and DT Midstream’s Blue Union Gathering System, which collects from the Haynesville-Bossier and Cotton Valley formations in northern Louisiana and East Texas (see Figure 3 below).

In contrast, most transmission lines operate at high pressure, using a series of compressor stations along the length of their systems which can sometimes span multiple states. Pipeline diameters typically range from 24-36 inches — but some are as small as 8-10 inches or as large as 48 inches. (Most of the recent long-line systems out of the Permian Basin have been 42 inches in diameter).

Permitting Speed: An important distinction enjoyed by a gathering system (and an intrastate transmission line) vs. an interstate transmission pipeline is the speed of authorization for construction, siting, or design. As noted earlier, gathering networks tend to have a smaller geographic footprint due to their usual clustered layout and are typically located in less-populated areas. More importantly, they carry raw, unprocessed gas, hence falling outside of FERC’s purview. (Similarly, intrastate transmission systems fall outside of FERC jurisdiction, which is the reason so many huge Permian-outlet pipelines have been careful to stay inside of Texas.) All these factors enable an operator of gathering and intrastate pipes to get their needed permits in as little as a few months, varying by the state or states involved, the size of the project and its complexity. On the other hand, interstate gas transmission pipelines can stretch for hundreds of miles and take at least 18 months — and sometimes much longer (like eight years and an Act of Congress in the case of Mountain Valley Pipeline; see Rescue Me) — to get the necessary permits from the federal government.

Although it might be easier to get permits for constructing a gathering system or intrastate pipeline, there are still some hangups. Under the NGA, permitted interstate pipelines get eminent domain, which grants a pipeline operator right-of-way access to the necessary land. Intrastate pipelines may or may not get eminent domain, based on the law of the state where they do business. Gathering systems just don’t get it at all, which can result in lengthy negotiations or legal battles with private and state owners of a property before gathering pipes can be laid. (This has become a serious issue for a couple of pipelines in Louisiana.) However, since gathering systems are usually built in association with production, right-of-way access often is just part of the royalty negotiations with landowners in the first place.

Despite the differences, here is one common area: All transmission lines can get bogged down with environmental challenges and reviews from state and local governments, and federal agencies like including the Army Corps of Engineers, which regulates pipes that cross U.S. waters, including wetlands.

Figure 3. Blue Union Gathering System. Source: DT Midstream

These challenges have spurred some creativity among midstream operators wanting to fast-track their access to more gas production and transport capacity without getting bogged down in the FERC approval process. Basically, to get the most relief from regulation, a new system that wants to be called “gathering” may try to connect to a processing plant that is as far downstream or as close to the transmission facilities or markets as possible.

Some of the constrained areas may also be served by gathering systems originating at production sites in one state and extending to processing facilities that are near the doorstep of demand centers such as the LNG supply heads and export terminals along the Gulf Coast — reducing the need for additional transmission lines. (Internally, we at RBN are debating whether to dub this phenomenon trans-gathering or gather-mission — let us know your opinion.) DTE Midstream’s Blue Union Gathering System, shown in Figure 3, follows that basic approach. But, as mentioned earlier, that strategy is not without its pitfalls. And even as creative juices pour forth, ultimately, it’s FERC that gets to decide what’s gathering and what’s transmission.

Beyond these types of systems that blur the lines, as more and more infrastructure is needed, we should expect to see additional efforts aimed at debottlenecking and expansion of existing pipes in places where production is likely to grow the fastest. It’s clear that new gathering and transmission capacity will be needed to marry expected increases in natural gas production to LNG feedgas demand on the Gulf Coast and companies will continue to pursue the best ways to move all that gas where it needs to go.

“Shall We Gather At The River” was written by American poet and gospel music songwriter Robert Lowry in 1864. The song was first recorded by the Metropolitan Quartet and released on an Edison cylinder (pre-vinyl) in 1917. The song’s lyrics cover the theme of reuniting with loved ones in the afterlife. It has been featured in a few western motion pictures over the years. It appears as the fourth song on side two of Willie Nelson’s 20th studio album, The Troublemaker. Personnel on Nelson’s version were: Willie Nelson (lead vocal, guitar), Dan Spears (bass), Bobbie Nelson (piano), Larry Gatlin (guitar, backing vocals), Paul English (drums), Mickey Raphael (harmonica), Jimmy Day (dobro), and Dee Moeller, Sammi Smith (backing vocals).

The Troublemaker was recorded in February 1973 at Atlantic Recording Studios in New York City with Arif Mardin producing. Its initial release was canceled after Atlantic Records closed its country music division. After the huge success of Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger album on Columbia Records in 1975, Columbia released The Troublemaker in September 1976. It went to #1 on the Billboard Top Country and #60 on the Billboard 200 Albums charts. One single was released from the LP.

Willie Nelson is an American country music singer, songwriter, guitarist, and actor. He moved to Nashville in 1960, and as a songwriter penned the hits “Funny How Time Slips Away,” “Hello Walls” and “Crazy” during this period. Frustrated by the Nashville country music business machine, he relocated to Austin in the early ’70s and became one of the key players in what was to become the outlaw country movement. He has released 100 studio albums, 14 live albums, 51 compilation albums, two soundtrack albums, and 180 singles. He has sold more than 60 million records worldwide. He has appeared in 36 motion pictures, and several television programs. He is a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, and the National Agriculture Hall of Fame. He won the Gershwin Prize from the Library of Congress and received Kennedy Center Honors in 1998. At the age of 90, Nelson continues to record and tour.

"gather" - Google News

January 11, 2024 at 09:00AM

https://ift.tt/Xhl1qKk

Shall We Gather At The River - Distinguishing Gas Gathering Pipelines From Transmission And Why It Matters - RBN Energy

"gather" - Google News

https://ift.tt/bjzaT4W

https://ift.tt/H12LJBF

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Shall We Gather At The River - Distinguishing Gas Gathering Pipelines From Transmission And Why It Matters - RBN Energy"

Post a Comment